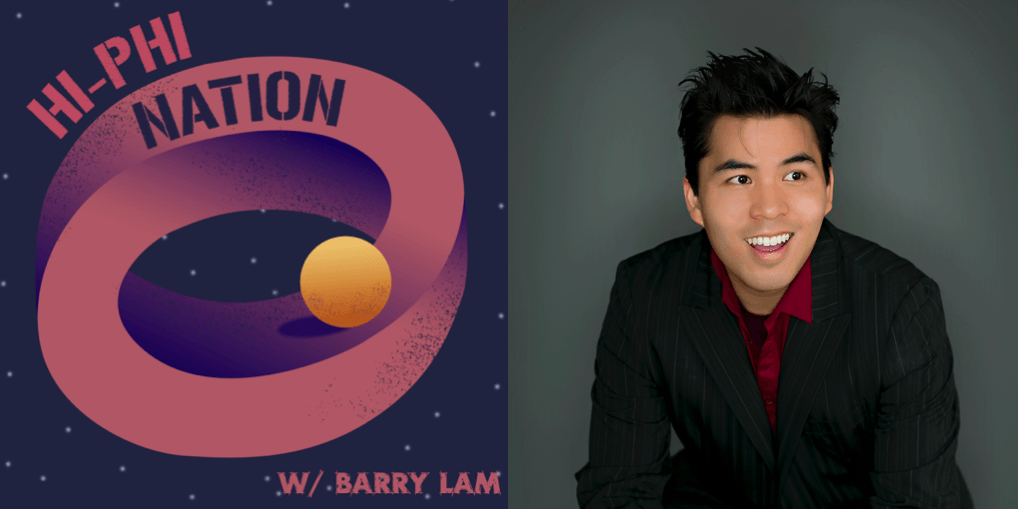

Barry Lam is a philosophy professor at Vassar College and the host of Hi-Phi Nation, a philosophy podcast that “turns ideas into stories.” I sat down with Barry at the end of last year to talk about his show, his planning process, and his own podcast listening habits. Our conversation revolved around episodes from the first season, but season two of Hi-Phi Nation, which began October 31st of last year and will run until May, is just as filled with exciting stories and ideas.

Odland: What made you want to make Hi-Phi Nation?

Lam: I’ve wanted a story driven show about philosophy since I started listening to podcasts in the first place. I saw so many shows out there dedicated to other areas of academia: Freakonomics, Planet Money, and everybody in business has their own podcast; Invisibilia started doing it for cognitive psychology. But there weren’t any philosophy shows. Philosophy encompasses a lot of things, so you could have a very long-term show and never run out of material. I’ve always wanted a show like that to exist, and when it didn’t come around I decided I’d be the one who makes it.

Odland: What production knowledge did you have before you started? Did you learn as you were making the podcast?

Lam: I was in college radio, so that gave me comfort with a mixing board, levels, mic placement — things like that. Everything else I had to learn. Everything. You don’t learn how to interview in college radio. I had to learn how to cut tape on digital audio. Sound tracking, I had to learn. The hardest part of the job is structuring. When you have fifteen hours of tape with three different voices, how do you structure that? The episode about love had a ridiculous number of people. I had to learn everything. The only thing I felt comfortable with was sound levels.

Odland: How did you go about planning that episode? Do you usually plan out your stories?

Lam: That episode was the hardest because the task I took on was way too big. The idea was to follow maternal love at various stages of life, thinking about mothering with newborns, then teenagers, and so on. So the first task was to find people at those different stages. To be honest, I didn’t initially have a plan for the kind of philosophy I wanted to talk about. I collected the tape then went to two philosophers who worked on love and I said, “Let’s see if we can talk about love at these various stages.” And of course the philosophers were very game for it. But their own work didn’t necessarily speak to it. My job was to try to put it all together. It was very much a matter of trying to make the philosophy fit the tape that I recorded. That was true of the Love episode the most. But it wasn’t true of other episodes. For a lot of them the philosophy came first. That was the case with episode one. I had a very clear thesis I wanted to push. I had to decide what was going to be the story for that episode. There’s a million of them to choose from, and I had to find the right one.

Want to receive our latest podcast reviews and episode recommendations via email? Sign up here for our weekly newsletter.

Odland: What’s your process for finding the people you speak to? How do you reach out to those individuals?

Lam: There are a lot of constraints when you don’t have much of a budget. One thing that’s a quick solution is that you try your best to find people within driving distance. In the first season, because I didn’t have much of a budget, that’s what I did. I was at Duke for the year, so North Carolina was in driving distance. I’m in Los Angeles for the holidays because of family. And I’m [based] in the northeast, but even given that, I flew places.

Odland: Were there any episodes that you started to make that just didn’t work out? When you found that happening, what was the obstacle that prevented an episode from being made?

Lam: A lot of them, and that continues. There are many different kinds of obstacles. Almost every episode you’ve heard is not how it was originally planned. You kill a lot of ideas. The ideas you kill could very well be because people decided not to talk to you, or because the people you did talk to only talked about a totally separate issue. Or it just doesn’t work as a story, or the philosophy comes across as too boring.

Odland: Do you feel like you’re still learning with each new episode?

Lam: By the time you make ten full-length episodes you’re pretty comfortable with the technical stuff. That’s pretty quick. The things that you never get fully comfortable with though — and I’m sure even Ira Glass is not fully comfortable with — are the things that you’re always learning: writing, voicing, structuring. Every story is different. If you follow a formula, things will get boring, so you try to mix things up. Sometimes you have to be humorous, but you write something and it falls flat, and you’re like, ‘Ah that’s not funny!’ You’re always learning to do that, and I’m still at the beginning. I don’t think I’m ever going to stop learning how to do that.

Odland: Can I ask what podcasts you listen to? What are you listening to right now?

Lam: 99% Invisible, Criminal, This American Life. I really like Love + Radio. NPR has a new show called Rough Translation — I really like that. I’ve been getting into this show called Switched on Pop, which is two guys doing musicology on current pop music. And I’m a fan of the Gimlet shows and the Radiotopia shows. My friend Chenjerai Kumanyika has a show out on Gimlet called Uncivil. That’s a great show; Chenjerai is fantastic.

Odland: Do you think how you listen to podcasts has changed since you’ve started producing one?

Lam: Absolutely. A great deal. Listening as an academic before any production is totally different because I know a certain amount of stuff, and I want to learn, so either a podcast is great because I’ve learned something, or I’m pissed off because I know about the topic and they didn’t cover this, or whatever.

As a producer, you listen for all of the edits. You listen for the structure. You recognize decisions that are made. I’ve become a lot more forgiving of people in their decisions. When I listen as a producer I recognize how hard it is to make something a certain way. But then, on the other side of it, I’ve become less forgiving when I genuinely think somebody has dropped the ball. Did you grow up watching American Idol?

Odland: I think I saw the first or second season.

Lam: In the beginning of American Idol, people were always saying Simon’s a dick. Except when somebody was good, Simon would say, “This is incredible.” I’ve gotten more like that. I’ll think, “Ah, this was flawed, but I understand and am forgiving of it.” Or: “This is genius. People don’t understand how wonderful this is.” But then I also think, “Wow, really? You’re this genius, but you should have done a lot better than what you did here.” As a producer, I have a more polarizing, but also more forgiving, attitude.

Odland: Lastly, is there any advice you have for people just starting out, who are wanting to make their first podcast?

Lam: The advice I’d give to those people is start making, learn as you make, and start right away. Don’t wait another week, just start. Just do it, and worry about it later. Don’t get bogged down in should I or why or whatever. Everything’s going to pass you by unless you just start doing it.