On the first episode of The C-Word, Lena Dunham and Alissa Bennett tell the story of how they met. It was in a bathroom stall, just prior to them starting at the same college. Dunham was crying because her hairless cat had just been put to sleep; Bennett, a model who would later become a curator and an “expert in celebrity deaths,” falls for Dunham because of the way everyone in their class constantly tells her to “shut up.” As the starting point of a friendship, it’s surreal. But as the beginning of a podcast that charts the media’s depiction of the public downfalls of misunderstood women, it sets the perfect tone of ostentation and satirical self-awareness.

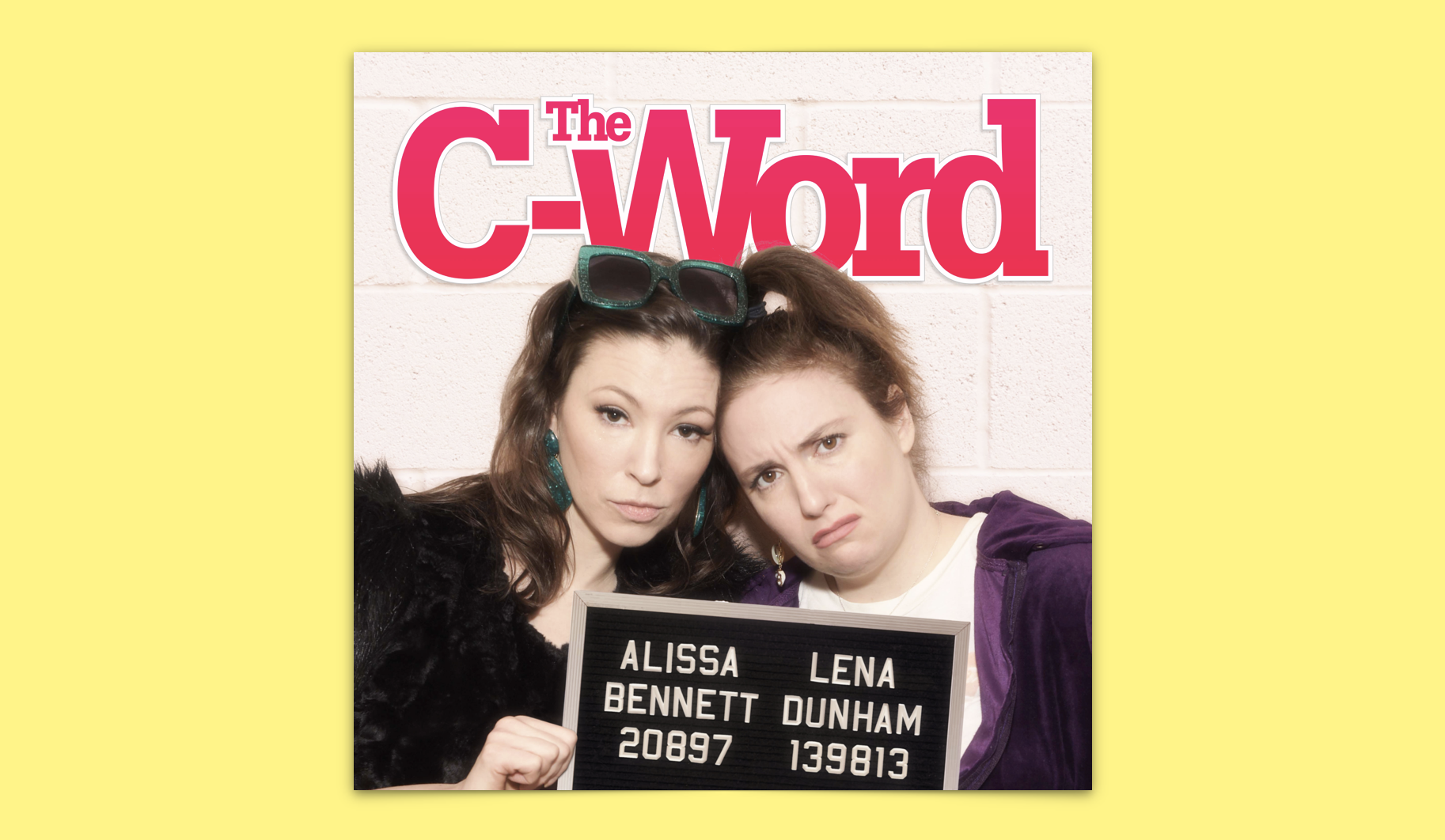

The C-Word. It’s not cancer. It’s not cunt. It’s not even conservative. The C-Word is crazy — except Bennett and Dunham promise to never call you that. As the buzzy new podcast from subscription platform Luminary, The C-Word reveals the effect of public scrutiny on Dunham, creator of the hit HBO show Girls and co-founder of the now folded Lenny Letter, particularly its impact on her self-image and behavior. There is little that Dunham does, either personally or professionally, that doesn’t cause friction in the media. Her experience of critique becomes an essential framework for the podcast’s subject: our culture’s tendency to dismiss interesting, difficult women as “crazy” when their actions become too abstract and challenging to empathize with. Almost predictably, the show is also a rendering of Dunham’s own complex identity. However, it is the examination of a particular world of privilege, femininity, and artistic performativity, illuminated by Bennett’s personal insights, that proves to be the podcast’s lasting effect.

The C-Word documents the uncomfortable reality of being a female artist in the public sphere through its hosts’ brief but telling anecdotes. They convey the reactionary response that a woman’s physical image can provoke, particularly when the owner of that body attempts to control the artistic symbolism behind its representation. By refusing to accept the mainstream narrative, The C-Word suggests that the motivations behind these women’s actions might be more complex than mere insanity. Their stance of rejecting the idea that these women are “crazy” is openly feminist, unapologetic in its interpretation of the unfair treatment of celebrity women in comparison to their male counterparts. Dunham and Bennett’s approach to the podcast is grounded in a conceit established somewhere outside of the show itself: that the incomprehensible behaviour of their subjects is, in fact, comprehensible. Just not to anyone in the media, their families, their partners, nor any man currently living. We could add Dunham and Bennett to this list, especially in light of their insistence that their interpretation of events is also incomplete. Yet, as a listener, I felt compelled to believe in their shaping of the narrative because ultimately it is their narrative too.

Want to receive our latest podcast reviews and episode recommendations via email? Sign up here for our weekly newsletter.

Being of a generation that bridged the movement from pre-9/11 experimentation and disaffection to the hypervigilance of digital media, both Dunham and Bennett have lived with the increasing deconstruction of their public personas. But it’s this expertise in grappling with mainstream critique that makes the show convincing. Dunham has often created and played characters that appear to mirror her in a way that becomes inseparable to the average consumer; yet this is a conclusion that Dunham has perpetuated through her own social media posts. The documentation of her illness as a visual testament is not just a way of reclaiming the discourse on unruly female bodies. It becomes a performative act in itself. The provocative tone is unavoidable, its statement of radical acceptance challenging us not to flinch.

Last year’s profile of Dunham by Alison P. Davis for The Cut highlighted potential reasons why Dunham might coalesce her reality with her art, even in her own mind. Davis pointed to Dunham’s upbringing amongst creatives and artists in the privileged yet alternative neighborhoods of Brooklyn. In the viral response to Davis’s piece, the consequences for Dunham of being profiled with such a degree of exposure was lost in her retreat from a consistent professional platform. She is currently recuperating from a chronic illness after an intense period of productivity. On the podcast, Dunham makes several references to the effect that the events of the last few years — the end of her longest relationship, the final season of Girls, her surgery — has had on her mental health. It becomes the most insightful part of the show, a survivor weighing in on the violence of public discourse. Her discomfort with Davis’s profile comes through, a palpable sense of vulnerability and even betrayal.

On episode five, which tells the story of fake-9/11 survivor Tania Head, Dunham speaks to the effect that chronic pain and trauma can have on someone’s sense of reality. She claims that it creates uncertainty around the parameters of the stories we tell ourselves, a disconnection from reality. In a culture of self-creation, particularly in globalized, image-conscious cities such as New York and Los Angeles, the notion of maintaining a mythology of personal authenticity while becoming one’s own provocative artistic persona might not be so far-fetched. Dunham has spent most of her personal and professional life in one of these places, and even her student films have dedicated IMDB pages. For Dunham to convey her personal experience through writing or acting risks the conflation of her characters with her real self; if her audience struggles to distinguish Hannah from Lena, or takes all her satire as sincere, to grow through her twenties with this lack of boundaries may cause the blurring Davis exposed in her profile.

In my research for this review, I came across an article in Document Journal titled “Curator Alissa Bennett Details the Dark Side to Lena Dunham.” One can read the piece and feel touched by this mutual investment in the self as Art Subject. However, it highlights that, despite Davis’s attempt to deconstruct the blurred relationship between Dunham and her artistic persona, whether she truly believes it or not, Dunham’s entire online presence is designed to obscure the distinction — and Bennett is onboard.

The podcast’s heart is located in the support that the friends and co-hosts provide each other. Bennett, who is older than Dunham, provides a secure, ironic wisdom that balances Dunham’s vulnerability. As the author of the popular biannual zine Dead Is Better, which compiles essays on our collective obsession with dead celebrities, Bennett’s expertise grants the podcast a degree of thoughtful curation. At the end of the eighth episode, the actress Jean Seberg has just died in her car surrounded by barbiturates and bottles of mineral water. Bennett asks the listener to question why we project destructive fantasies onto women like Seberg. By viewing women as fantasies, Bennett argues, it becomes easier to believe the rumors and slander surrounding them.

The episode on Seberg clarifies Dunham’s co-host as essential in the success of the podcast’s format. Its tone is satirical and dry, yet underpinned by a sincerity that Bennett affirms even in the most alienating moments of the conversation, such as her description of being scouted at seventeen, or marrying and divorcing the same man, twice. Bennett also brings a distinctive LA atmosphere to the show, a borderline trashy cacophony of name-dropping and pop-cultural references. It creates a sepia-tinted haze, evoking the novels of writers like Dana Spiotta or Emma Cline. The presence of this feeling means the most successful episodes are the ones featuring women who belong to this period and place. The first two episodes, on Casey Johnson and Robin Givens respectively, are some of the best; the women’s stories are entangled with the insubstantiality of television and the fickleness of Hollywood culture.

An odd departure in tone comes in the examination of Lizzie Siddal, a pre-Raphaelite model whose notoriety for complex mental health issues was second only to her period-defining beauty, becoming an object of fixation for some of the most prominent romantic painters of the age. Although not the ideal fit for the show’s tonality, the episode demonstrates The C Word’s range while illustrating the obvious tragedy that the fantasies we create around women are a problem which vastly predate contemporary media. As it becomes clear that Bennett embraces the enigma of Dunham’s own indistinct identity, so emerges the question of whether enough fans of Dunham’s work will also accept the lack of clarity around the realities and fictions of Dunham’s public life. Perhaps the answer is reliant on the trends of online punditry. Will nuance emerge from the shadow of the reactionary?

In the Document article, Dunham asks Bennett whether she feels it is important to be a “good” person. Bennett answers:

“I think it’s important to be empathetic. Lately I have been really frightened by what being a ‘good’ person means . . . Is it bad that I am obsessed with overdose deaths and murder? I think it is getting progressively more dangerous to frame ourselves in these terms, and maybe goodness has to be considered in really simple ways.”

The internet is inundated with criticism of Dunham — of her work, her appearance, her personal life. Many people, rightly, call attention to her ill-advised comments and sometimes regrettable takes on race and the rape allegations facing a Girls writer. Yet it has become impossible to address her new projects outside of these mistakes. What Bennett highlights in her answer is that we have become obsessed with determining whether Dunham is “good” or not. She is flawed, yes. But she is also a genuine talent, and like the subjects of her podcast, we struggle to view her work in isolation the way we manage to do with a number of male artists. If we become confused about the difference between a man’s real personality and their on-screen alter ego, it is typically a positive. No one is criticising Jackie Chan for promoting violence. Robert Downey Jr. and the characters he portrays are indistinguishable. We risk moving too far in the other direction, of forgiving celebrity men for outrageous behaviour because it suits our narrative, our collective understanding of them as infallible, misunderstood superheroes. In episode two, The C-Word points to Mike Tyson biting off someone’s ear and still being considered as a rascal with a heart of gold. More recently, the controversy over Liam Neeson’s admission that he wanted to kill a black man as retribution was shocking for many reasons, not least because it seemed to fit too neatly into Neeson’s on-screen identity. Whether his mistake will affect his legacy is yet to be seen, but he currently has three films coming out this year and two in post-production.

In the recent episode on Miranda Grosvernor, a woman who concealed her identity to befriend powerful men in Hollywood over the telephone, the show encounters a new angle on the nuances of subversive female behaviour. Until this episode, most of the women profiled on The C Word have been highly attractive, the type of people using or being used for their image. The notable exception to this is Tania Head, whose discomfort in her own body and desire for the recognition given, typically, to beautiful women led her to manufacture a new identity around being a survivor of 9/11. Head used this lie to make herself visible. She wanted to be seen in a society that ignored her because she wasn’t pretty. But Whitney Walton, aka Miranda Grosvernor, didn’t want to be seen. The public, even after the revelation of her deceit, never laid eyes on her. Reports of her unattractiveness are secondhand, likely inflated to contrast with the slim, college-aged blonde she was impersonating. Important, wealthy men were obsessed with Walton, but they’d never actually looked at her. They spoke with her hour after hour, day after day, captivated only by her voice. They fell in love with her personality. By removing her visuality, Walton was simultaneously freed and trapped. She could engage with men who otherwise might not have given her a second glance, but she was also victim to their desires, unable to exist outside of their “dream girl” expectations once the illusion was shattered.

Dunham also contends with these issues in her public persona. Through her writing, she should theoretically be untethered to the physical expectations of femininity. Yet much of her work also exists in visual mediums. By choosing to star in her work, such as Tiny Furniture (2010) and Girls, how Dunham looks becomes essential to her brand. She will never be invisible; from her sprawling fairy-tale tattoos to her unapologetic nude scenes, Dunham’s body has become a statement of political intent. To disappear behind her words, as Walton did, is not an option. When we acknowledge that critique of her work and beliefs has become entangled with critique of her body, we might be more sympathetic. Being an artist is a condition that already coalesces these boundaries. Being a female in the public consciousness, according to her podcast, turns this fluidity into vulnerability.

The C-Word is not crazy. It’s maddening. It’s psychotic. It’s all the hyperbolic insults that have ever been thrown at Dunham on Twitter. As entertainment, The C-Word is as unsettling as it is compelling, causing the listener shift uncomfortably in their chair — a pop-culture testament to women who weren’t given the benefit of empathy. Perhaps, The C-Word suggests, this is a courtesy we should all extend more often.

¤

Alice Florence Orr is a writer based in Edinburgh. Her work has appeared in Scottish Review, Like The Wind, and Nomad Journal. You can connect with her on Twitter or Instagram.

(Credit: Luminary)

(Credit: Luminary)