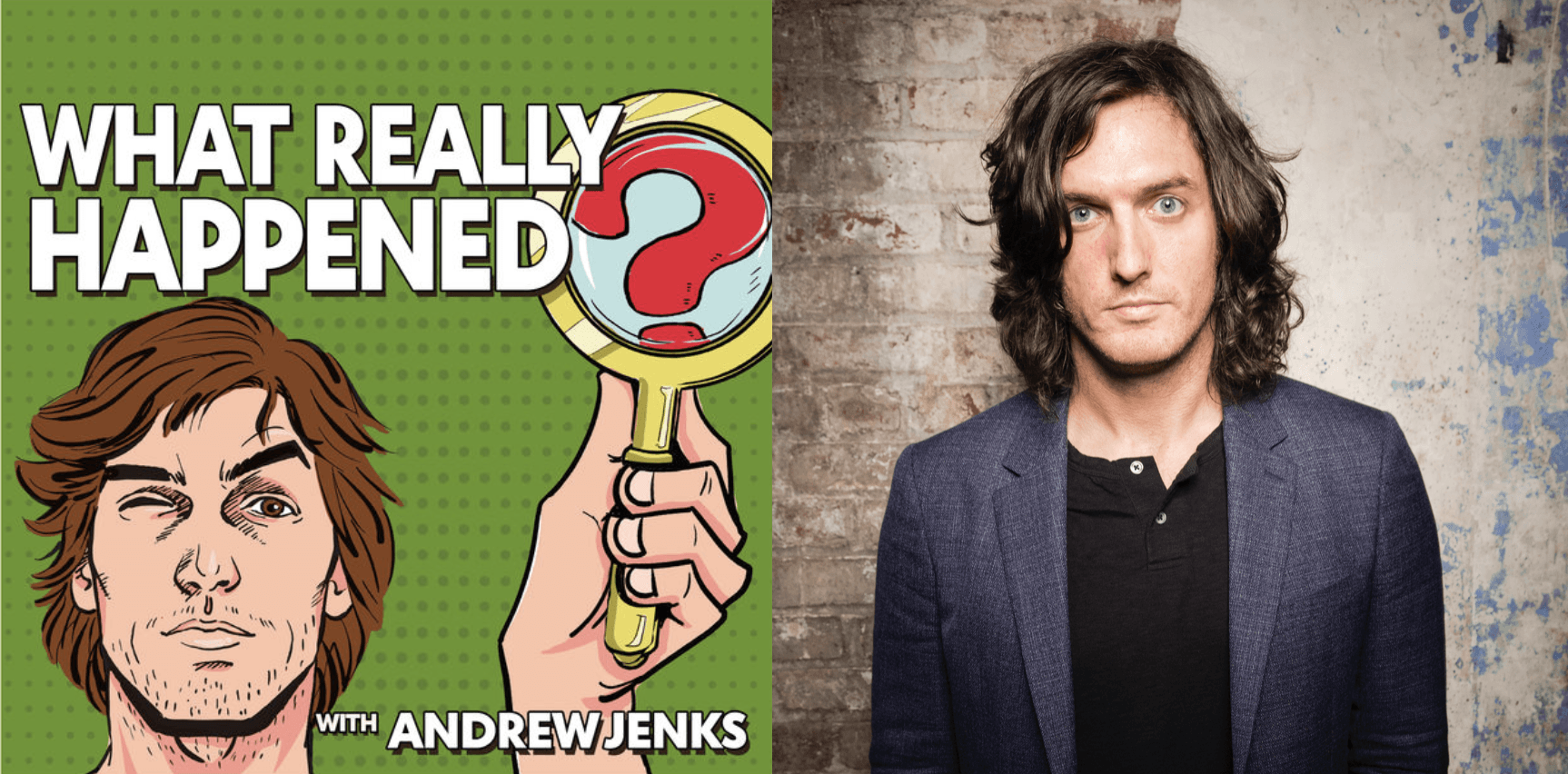

After creating documentaries for HBO, MTV, and ESPN, the award-winning filmmaker Andrew Jenks is now telling stories on his podcast What Really Happened? In the show, Jenks aims to challenge preconceived notions of historical events — events that range from when Britney Spears shaved her head, to the use of sonic weapons in Cuba, to why Michael Jordan really retired in 1993.

What Really Happened? is rooted in factual storytelling. Jenks is not out to embellish or dramatize. Rather, he conducts extensive research to understand the truth behind these events, and explores how it must have felt to really be there. We spoke with Andrew about the process of making an episode, the origin of his empathy, and how he involves his listeners in the show.

What kind of a stumbling blocks do you encounter when you’re doing research? I noticed in many episodes — take the one on Balloon Boy, for example — people don’t really want to open up.

With the Balloon Boy episode we ended up interviewing my friend Matt Heineman, who directed Cartel Land and now has a great movie out called The Private War. I was roommates with him 10 or 11 years ago, when we were both fairly broke. If you had told me at the beginning of researching Balloon Boy that I would end up talking to Matt, I would have said, well, what the hell happened? But I think a big part of this process is if you aren’t open and able to lean into being wrong about what you first thought, then it won’t be good. Matt has this line — which I believe is Albert Maysles’ — that “if your story at the end is the same as when you first started, then you weren’t listening in between.” I really took to that because I realized it was true with the projects that I’d done in the past that I thought I did a decent job with, and that it wasn’t true with the projects I’m not particularly proud of. So I think if you’re hesitant or resistant to that, it makes things a lot harder. If someone says they’re not interested in talking to me, I don’t see that as a negative; instead, it opens up a world of other possibilities you can go down.

Does it work differently when you’re researching something recent? How does researching Britney Spears or Serena Williams differ from researching King John II or your episode set in the 1860s?

It’s surprisingly similar. Sure, with Britney Spears, you can reach out to a bunch of people that are intimately involved in the story, whereas with King John II you obviously can’t talk to anyone who’s alive. But in fact, no one — at least when I first started the project — had even written a book or an article about him. So I started by talking to historians who were familiar with the Middle Ages and specifically the Hundred Years War. Then I tried to get bits and pieces from historians who had written about figures who had come across John II, trying to learn different pieces of his personality. Ultimately I found a historian who had written a textbook about John, and he had a totally different interpretation of what he found to be his accomplishments that stood in contrast to the idea that he was of the one of the worst kings of all time.

Want to receive our latest podcast reviews and episode recommendations via email? Sign up here for our weekly newsletter.

Whether it’s Britney Spears, a king from the Middle Ages, or a Native American warrior from the late 1800s, it’s ultimately about doing a lot of reading and then tracking down the right people to speak with.

Your background is in documentary filmmaking. If I asked you who your filmmaking inspirations are, you could probably list a good number. I’m curious though, what podcasts gave you inspiration?

I’ve listened to a lot of podcasts to get an idea of how they went about approaching it, but I don’t necessarily listen to podcasts that are similar to ours. I’ve definitely listened to Revisionist History, which I know What Really Happened? get compared to, but I think they’re very different.

I loved S Town. Talk about a story that was changing and what a good job they did of following that change and not being resistant to it. I thought the show was so well done. And I like Marc Maron’s podcast. I’ve probably listened to his interview with Anthony Bourdain three or four times, because there’s always something new that I get from it.

Something unique to your podcast are the listener feedback episodes. Did you plan to do that from the start? It’s really cool to involve your listeners and let them shape an episode. What prompted that?

The idea came from working on the Mohammed Ali episode and trying to sort out what happened when he helped this guy who was threatening to commit suicide. We couldn’t track down a couple of individuals that we really wanted, so we thought, OK, we’re hopefully going to have a lot of listeners, so maybe they can help. It then evolved into the format we have now, where listeners or people who are part of the story but weren’t involved in the initial episode could take part and, as cheesy as it sounds, become a voice of the podcast.

It almost seems silly not to get our listeners’ opinions. That was really the thinking behind it. Now we have what’s called “The Contributors,” which anyone can sign up for on our website. We have people from all over the world giving me feedback on the episodes, whether it’s on the music or certain historical details, which is really helpful. I love telling stories. I’m lucky enough to be able to make a living doing that. If I’m going to be telling a story about something I’m not an expert on, I want to be open to other people chiming in.

Your projects are really tapped into empathy. With “What Really Happened?” you stay objective, but you’re also able to convey that these are real people with real lives. How do you go about balancing objectivity with that level of emotional nuance? Do you think that’s a skill you gained through documentary filmmaking?

I appreciate you saying that. Well, when I was a kid, my dad was in the United Nations and my mom was a nurse. I remember sitting at the dinner table every night and my mom would ask my dad how his day was. And he’d say, “Well, there’s a genocide going on in Rwanda and if we don’t get X amount of dollars or make a certain number of moves by Friday, millions of people will die. Then he’d ask my mom about her day. And my mom would say, “Well, there are a bunch of patients right now who are HIV positive and they can’t afford the right medication. But I’m thinking if I find a way to get this medication, we can save their lives or extend them by a couple of years.” At the time, I didn’t know what was going on, but looking back on it, I think that never left me. I’ve always felt the sense that there’s a lot going on in the world and that many people don’t have a voice. I’ve never escaped that.

Do you get a lot of feedback from the subjects of your episodes, people that were heavily involved in the story?

It varies. One thing I’ve learned from working on documentaries is that most people aren’t looking to have a story told about them. The senior citizens that I filmed for my first movie couldn’t care less about the cameras. They were interested in friendship and hanging out. And I don’t think Dave Chappelle necessarily cares about my take on what happened. If he hits me up, that’s cool. But I’m definitely not waiting around for it.

One thing with podcasts is that a single episode can feature a number of different topics and that within each of these episodes there are people who know these topics incredibly well. So, you’re always at risk of getting called out for saying someone’s name wrong.

So something I was really happy with was when we came out with a 1 hour and 50 minute episode on these sonic attacks in Cuba. I was a bit worried when we put it out there. We had talked to guys who were in the CIA. We had talked to a Cuban ambassador. We had talked to neurologists. We talked to a lot of people who could have been like, you got some of this wrong. But then we got a few emails from people involved saying they could see why this podcast does well. That felt really good because these were serious people who know their stuff.

What can we expect this season and in the future from “What Really Happened?”

An episode I’m really excited about is the one on the famous situation room photo when Bin-Laden was killed. There’s the photo of Obama in the backdrop and Hillary Clinton in the foreground. Secretary Bob Gates is there. We started looking into what was really going on in that room. What were they talking about during the raid? What were they doing before? What were they doing after?

It’s interesting because a lot of the main players have written books or talked to “60 Minutes” about it. So we talked to some of the people that you wouldn’t know by name. We talked to the guy whose shoulder is in the photo, and we get his perspective on what happened. We’re also working on an episode about why Kawhi Leonard left the San Antonio Spurs, and one on this incredible female Native American warrior who killed General Custer. Well, I shouldn’t say killed, but there’s some thoughts out there that she did. So it’s really a wide range. Hopefully they’re all good stories at the end of the day.

Does that mean this is your main gig for the foreseeable future? Do you see an end in sight?

As long as people keep listening, I don’t see why I wouldn’t be doing this. It’s just raw storytelling, it’s campfire storytelling. There’s nothing more exciting for me than to be challenged every week to tell a good story.

https://radiopublic.com/what-really-happened-WPR4ew

¤

Elliot Morris is a writer based in Utah