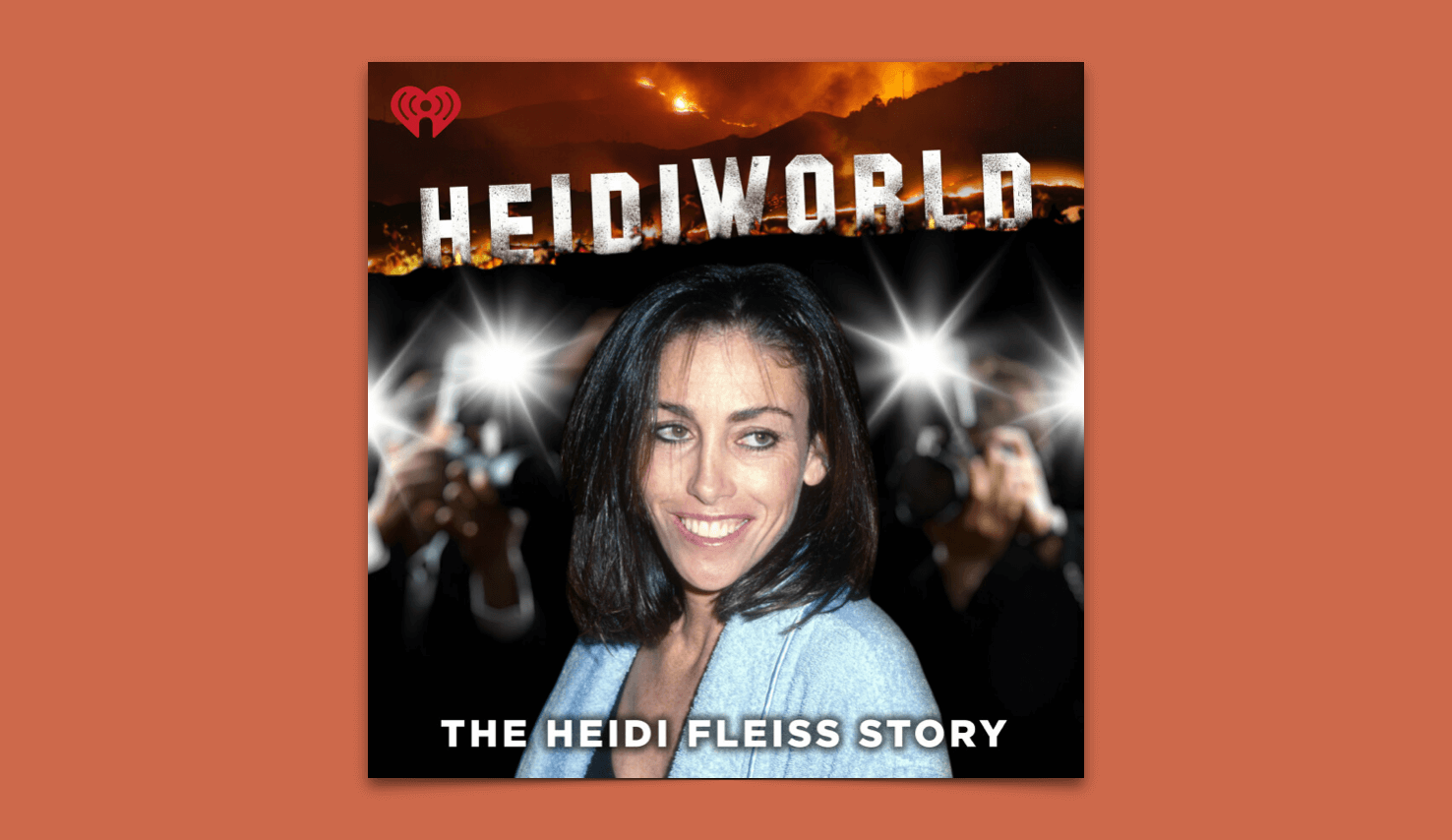

The legacy of Hollywood Madam Heidi Fleiss won’t stay hush. Last spring at New York’s No Gallery, artist Valentina Vaccarella exhibited Risk Management, a mixed-media painting in which Fleiss, sporting orange shades and a defiant smile, poses before a backdrop of trading-floor stock tickers. The image captures Fleiss’s hustler brand, but it also appears ripped like a scrapped tabloid page, suggesting that Fleiss’s story remains distorted and obscure. Molly Lambert’s latest podcast from iHeartRadio, HeidiWorld, fills this gap in cultural history with a digressive ride through LA’s underworld.

Lambert previously co-hosted the podcast Night Call, a call-in program at the intersection of pop culture and conspiracy theory. HeidiWorld follows a similar course, in that Lambert develops Fleiss’s connections to seemingly everything in 90s LA to an almost conspiratorial extent. As Lambert noted in an interview with Elle, Fleiss’s story reveals how the vice industries and popular culture are inextricably linked, and that Hollywood is no less a grift than the shadow economy it relies on. The format of HeidiWorld threads Lambert’s narration with a small army of voice actors whose lines are drawn from media contemporary to Fleiss’s scandal: magazines, TV segments, books, newspapers. In the background, a jingly synthpop theme alternates with smoky interludes of acid jazz. And throughout HeidiWorld, Lambert uses Fleiss’s case (“a classic American story about one of the greatest hustlers of all time”) to argue for the full decriminalization of sex work.

Fleiss was born in LA in 1965 to Paul Fleiss, a Jewish pediatrician, and Elissa Ash, an elementary school teacher. A lackluster student and realtor, Fleiss entered into sex work under the prominent Madam Alex at age 22. Within three years she cut ties with Madam Alex to start her own escort service, distinguished by an exclusive, high-end brand. Lambert carefully sorts the politics of Fleiss’s work as a madam: her girls were well-compensated and empowered to do only what they wanted, but Fleiss also at times prioritized her profits over their safety. Fleiss may have been exploitative, but no more so than most other employers under capitalism. Lambert maintains that sex work is criminalized not out of humanitarian concern, but because prohibition is more profitable than allowing sex workers to claim the means of production.

In 1993, Fleiss was arrested in a Los Angeles Police Department sting operation, and stood trial on charges of pandering and tax evasion. Lambert notes that Fleiss’s trial unfolded amid, and contributed to, a new media environment of tabloids, 24-hour news cycles, and court TV. The constant coverage bent to reactionary forces that cast Fleiss as a criminal, while her male clients like Charlie Sheen, who testified against her, were just being men. Lambert criticizes how the trial and its coverage conflated sex work and sex trafficking, a misconception that persists today in legislation like the FOSTA-SESTA package. HeidiWorld also reserves moral complexity for its difficult characters: even as Lambert criticizes the men who vilified Fleiss, she also sympathizes with them. For instance, Lambert argues that Sheen’s family background and social environment fostered his addiction and womanizing, coolly asserting that “in our deeply misogynistic society, masculinity is a prison too.”

While Fleiss was in prison, the Internet exploded and the media landscape changed yet again. The same morbid curiosity and prime-time stream of lurid details that made Fleiss famous set the template for early reality TV like The Real World and Big Brother. Fleiss herself would later appear on Celebrity Rehab and Celebrity Big Brother, and in 2002, Heidi’s cousin Mike Fleiss created The Bachelor amid a post-9/11 boom of reality TV and amateur porn. The familial resemblance between the show — in which a wealthy man chooses from a stable of attractive women — and Heidi’s business is not lost on Lambert. It seems Americans will permit public degradation so long as they can watch it. Although here, again, Lambert rejects the idea of moral purity: “there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism, so you might as well take it to the danger zone.”

Given Fleiss’s role in the advent of new media, it makes sense to tell her story on a podcast. For one, Fleiss worked and made her name through the telephone (she was, after all, a call-girl); before anything else, she must have been a devilishly effective talker, like the Hollywood men around her. This fact lends her story to the gossipy podcast, as the medium offers the naked voice in all its unseemly charm, a quality that actress Annie Hamilton uses irresistibly in her performance of Fleiss. Lambert also claims for herself the verbal bite she identifies in Fleiss: over the course of ten episodes, her breezy narration and commentary never lose interest and sophistication.

After her prison stint and forays into apparel and publishing, Fleiss moved to the Nevada desert, where she lived for 15 years before a recent move to Missouri. Her plan to start a stud farm flopped, and she instead started caring for a flock of macaws inherited from her neighbor, another ex-madam. Fleiss’s flashy rise and drawn-out downfall offer no neat takeaway, tracing the underside of American decency and aspirations. Fleiss was an outgrowth of third-wave feminism, more concerned with money and power than virtue and equality, and if there’s a crisis in contemporary feminism, her brand of shameless hustle may represent a recent-past alternative. She also predicted our social media world, where “as long as you can keep people’s attention, that’s all that really matters,” as Lambert says in Elle. Fleiss’s relevance is about the very compromise and struggle of staying relevant, even as the world burns around you until all that’s left is the desert.

¤

Christian Prince is a writer based in Washington, DC. You can reach him at [email protected] and on Instagram.